Democratic New York: The Vision of George Forss and His Collaborators in Pre-9/11 New York

As a street vendor peddling his artwork, George Forss describes the market of the streets: “For me, it was crazy people in the streets, and I was fascinated by odd doorways. But I didn’t find anyone buying them; I had to learn that the hard way. In my line, selling in the street, I learned a lot. You have a store, something sells, you get more stock of it. Something doesn’t sell, you don’t stock it anymore.”

It is in this way that Forss begins to document New York, in constant conversation with his always-changing customers, who are merely people walking past him on the street. As his customers buy, they vote, and Forss shoots and stocks what they choose, forming a sort of democratic process. What emerges is a body of work that quintessentially captures New York, a collective envisioning of the city by Forss and by the community that surrounds and patronizes him. Ultimately, this culminated in a book with the uncompromising title New York/New York: Masterworks of a Street Peddler, presented by David Douglas Duncan.

We Laugh We Cry 1995

Ten years later, Forss enters into another project, “The Access Project,” in which his representing gallery, Park Slope Gallery, uses its connections to get him access to some of the most stunning and unexpected views of New York. Again, Forss finds himself in another creative collaboration; Park Slope Gallery’s clientele relate that they can help to gain access to a particular view and Forss uses these opportunities to make the views his own. For example, when taken to the rooftop of St. Vincent’s Hospital for views of Greenwich Village, Forss instead finds the whimsical, unexpected St. Vincent’s Garden, a mural of flower graffiti.

The photographs that develop define New York conceptually as well as at a specific moment, the 1990s. Forss is confronted with the city’s most admired buildings and skylines, yet still manages to bring a freshness and sense of wonder. Forss’ extraordinary vision gives some of the best documented sites—the Statue of Liberty, the World Trade Center Towers, the Chrysler building—the newness of a child’s vision, but matched with the technical precision of a master.

Photographs that play with reflections, visions partially obscured or complicated by railing, the relation of things in the foreground and background, and double and triple exposures all bring a new way of looking to icons that culture bombards us with as symbols of New York. Forss takes and recontextualizes the common to bring a new sense of imagination to the quotidian landscapes as well as to the hidden pockets of the city.

In Forss’ re-imagined New York landscape, watertowers (West 17th Composition Uptown) exist alongside an exclusive view of Bryant Park from an upper level in the Grace building (Bryant Park/From Grace). In the image WTC/Watertowers, a trick of scale makes it appear as though two watertower siblings are nearly as monumental as the Towers. Foregrounding the water towers instead of the more “important” architecture, Forss allows us to view the city differently.

The innocence and fresh view that Forss brings to these photographs seems particularly fitting now, when one cannot help but look back at these photographs as documents of the city before the horrific events of September 11, 2001. The World Trade Center Towers now mark Forss’ photographs as part of a different era. The project itself, a collection of networked accesses to exclusive buildings and places, seems impossible in the contemporary climate—that trust is now lost.

Forss takes and recontextualizes the common to bring a new sense of imagination to the quotidian landscapes as well as to the hidden pockets of the city.

The relationships of trust that define Forss’ career—laying his artwork out on the street, gaining access to highly secured buildings and rooftops—are now extinct. Although the sense of coming together, community, and patriotism is often commented upon in relation to the response to 9/11, this project is an emblem of cooperation and community before the tragedy and the ideal city that Forss was able to capture and express.

As has often been commented about Forss, who has led a life with no small degree of adversity, his work is never a reflection of that. As he explains, “Sure, I have a lot of resentment, but it’s not going to show in my work. I want to be uplifted, and brought to the level of a beautiful place. I’m a romantic, and proud of it. I think of myself as a person who is almost on a campaign to show what our city might be like. When I’ve sold pictures on the sidewalk or at an outdoor art show, and I’ve seen people’s faces light up with pleasure, this has made me really happy.”

Instead of anguish, it is a sense of beauty, awe, and wonder that emerges from the most monumental to the most obscure places. Forss transforms modest, quiet, and hidden places into some of the most expressive photographs, such as We Laugh We Cry, another rooftop graffiti piece that was done at an abandoned grain terminal.

As Forss contemplates landmarks and obscurities, his photographs write his own geography. Part of creating what New York “might be like” is imagining only what can be in a photograph. His practice is marked by experimentation and also what he calls research: “I found I had an ability for research. You know, research doesn’t require knowledge, if you don’t know something, then you find out. And I experimented.”

Forss has experimented on every level to create this body of work; he has made his own box camera, tweaked the process for developing negatives, and created various physical illusions. It is this research, approaching things without preconceived ideas, that has created such a sense of innocence in Forss’ photographs—the ability to look at New York anew. In Reflections/Brooklyn Skyline/FDR Drive, Manhattan and Brooklyn are collapsed in a condensing of building and skyline and river. The result is a complex and impossible geography.

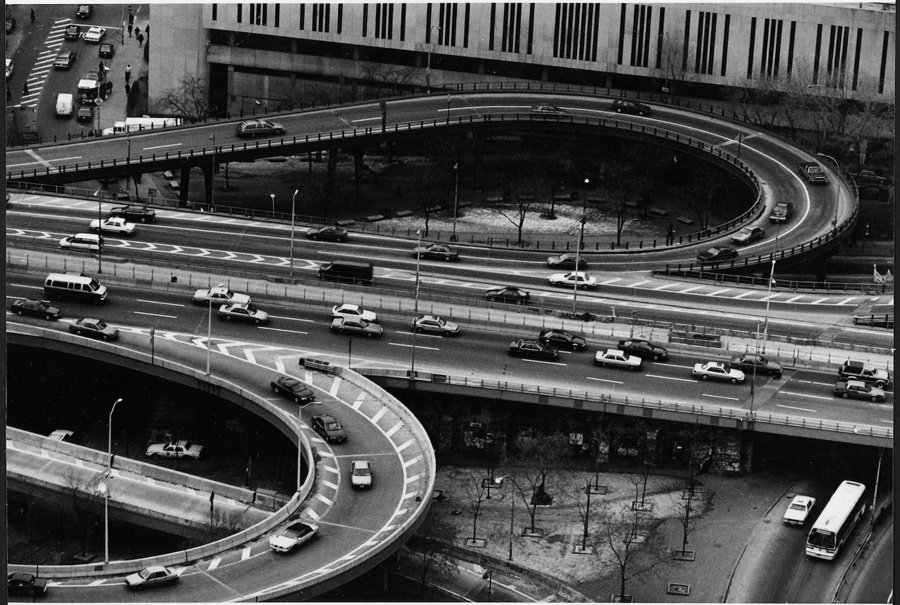

It is an aesthetic of playfulness and joy that emerges from these novel images of the city. July 4th No. 1 Time Exposure is also a product of this experimentation. Here, the time-lapse image captures a city alive. That it is July 4th seems almost irrelevant—in this image, the city is awake and full of excitement. The geometry of the loops in Which Way to Brooklyn? brings fun to one of the most mundane aspects of New York: traffic.

The Access Project unwittingly defines a carefree time in New York right before its most devastating and transformative tragedy. The collaboration and community that are embedded in the process of creating Forss’ work, coupled with an innocent and ever-curious eye, resonates with viewers even more now. These images are now nostalgic documents of a past New York—and also a New York that might be.

Faith Holland

Gallery Assistant

Park Slope Gallery Newsletter, Fall 2010 – Winter 2011, Volume V, Issue 1